Improving Rapid Naming With Targeted Cognitive Intervention

May, 2025

Rapid Automatic Naming (RAN) is the ability to quickly process and name aloud a series of familiar things - numbers, letters, colors, or objects. It is one of many underlying abilities that together enable cognition. Alongside phonological processing weaknesses, RAN weaknesses are the other key basis of “double deficit” dyslexia. As Maryanne Wolf writes in Proust and the Squid, “RAN tasks are “one of the best predictors of reading performance” across all tested languages”.

Cognitive researchers have long believed that RAN is a trait that changes little over one’s life. That is to say, if you are in the 50th percentile among your peers, you will remain near the 50th; if you are in the 25th you will remain near the 25th, and so on. However, our experience at the Carroll School in general, and with Targeted Cognitive Intervention (TCI) in particular, shows that RAN is actually a skill that can be strengthened. In other words, it’s more like running, which can improve with practice, than like eye color, which just is what it is. Carroll’s data is among the first showing the mutability of RAN, and as such some may find it controversial. However, given RAN’s importance for reading, this is a critical finding which deserves further study.

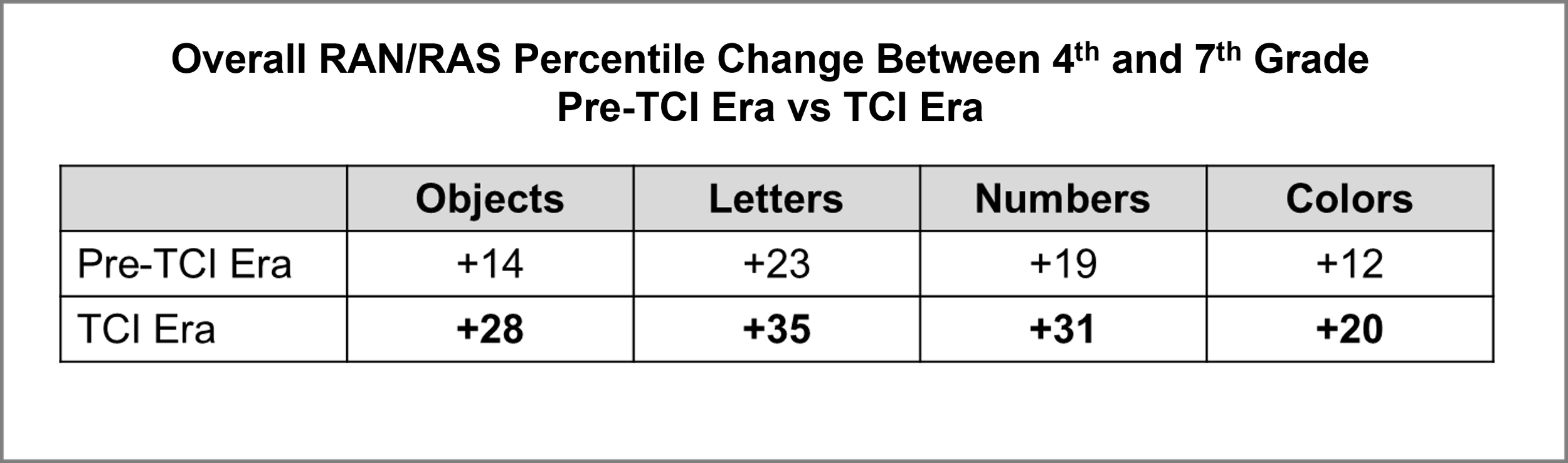

The experience at Carroll is illustrated by the chart below (Figure 1). The blue line shows the improvement in RAN for students at the Carroll School before TCI was introduced. For simplicity, the figure only shows the improvement in RAN of numbers; however, the Orton-Gillingham-based instruction at Carroll enabled significant gains in all aspects of RAN (Figure 2).

The red line illustrates the even greater improvement in all aspects of RAN for students at the Carroll School once TCI was added. Moving from the 11th to the 42nd percentile is a truly dramatic gain.

The figures focus on students who are weak at RAN (initially below the 25th percentile) because TCI has the most RAN improvement for those that are weak. Those that were already strong (above the 50th percentile) stayed strong but RAN was not significantly strengthened.

TCI does not directly teach reading nor train RAN skills. TCI builds cognitive capacity so that good instructional practices can be more effective.

Figure 1: Progress of Carroll School Students with Initial Weakness in Rapid Naming of Numbers, 2009-2019

Figure 2: Change in RAN Percentiles for Carroll School Students with Initial Weakness in Rapid Naming, 2009-2019